Dijkstra was right — recursion should not be difficult

Almost every programming language has various control structures like if…else/switch… case blocks and iterative structures like for and while loops. Most new programmers learn iterative control structures first.

But there is another very powerful control structure: recursion. Recursion is one of the most important ideas in computer science, but it’s usually viewed as one of the harder parts of programming to grasp. Books often introduce it much later than iterative control structures.

The number of questions on the web asking why recursion or recursive programs are so difficult to understand may give you an impression that recursion is indeed an advanced technique. But it does not have to be difficult.

Although recognizing the recursive nature of a problem and coming up with a solution requires a bit of an instinct, it can be learned through practice. This article will introduce and explain a number of topics and ideas that will help you when practicing recursive problems.

Why use recursion?

You might have heard this joke — to understand recursion you must first understand recursion. It goes in line with a common definition of recursion as a function that makes a call to itself.

Such a definition may give you the impression that such calls lead to an infinite regress, but the properly defined recursive solution is never infinite. This is because a recursive sub-function never solves the exact same problem as the original function, but always a simpler version of an original problem. At some point, this version becomes so simple that it can be solved easily and that is when a recursion ends.

This leads us to the most important use case for recursion: use recursion to reduce the complexity of a problem at hand.

Let’s see an example. Suppose you want to calculate the sum of all elements in an array which has nested sub-arrays. So that if a function receives the following nested arrays:

[1,[11,42,[8, 1], 4, [22,21]]]

it returns the sum of all elements:

1+11+42+8+1+4+22+21 = 110.

The trick is to identify and solve the simpler problem, then express the problem in terms of that simpler case. Then you apply recursion until that case is reached and solved. And with that, all other recursive steps up to your original problem are solved as well.

The simplest case of the problem at hand is an array without nested sub-arrays. For such an array the computational function may look like this:function sum(a) {

let result = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result += a[i];

}

return result;

}

assert.equal(sum([1, -5, 100]), 96);

Now we have the function sum that takes an array and returns a sum of all its elements. Let’s solve the original harder problem. It states that some elements can be arrays, while the current implementation assumes that all elements in an array are numbers. So we just need to check whether an element is an array or not, and if it’s an array, we already have the function sum to calculate the sum of all elements in that array. Let’s tweak our sum function a bit:function sum(a) {

let result = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

if (Array.isArray(a[i])) {

result += sum(a[i])

} else {

result += a[i];

}

}

return result;

}

assert.equal(sum([1,[11,42,[8, 1], 4, [22,21]]]), 110);

That’s it. We solved a simpler problem first and then used that solution for solving the harder problem. This task can also be solved using iterative solution, but it’s way more complicated because we would have to nest for loops but don’t know how deep they are nested. The unknown number of nested loops is a common characteristic of all problems that are recursive in their nature and should give you a hint that recursive solution is required.

Besides helping to reduce the complexity of a problem recursion has another important capability which is the ability to backtrack. The problems that require backtracking are usually concerned with walking trees/graphs, for example, different kinds of mazes. Such problems are solved one step at a time. Here’s the general algorithm:

- If the current step of the algorithm is the solution to the problem, return the result.

- If the current step is not a solution, see if there are other places to go from here.

- If there are remaining places to go, choose one and go there to see if it’s a solution.

- If out of places to go — backtrack.

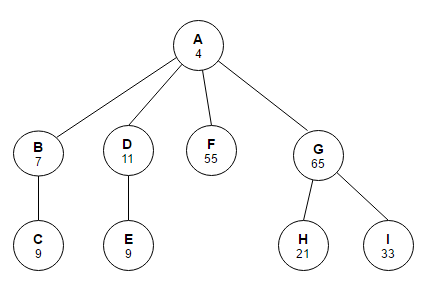

Let’s see an example. We are given the following tree:

It’s represented as nodes with children:let tree = {

name: 'A',

value: 4,

children: [

{

name: 'B', value: 7,

children: [{name: 'C', value: 9, children: []}]

},

{

name: 'D', value: 11,

children: [{name: 'E', value: 9, children: []}]

},

{name: 'F', value: 55, children: []},

{

name: 'G', value: 65,

children: [

{name: 'H', value: 21, children: []},

{name: 'I', value: 33, children: []}

]

}

]

};

And the task is to find a node with the value 21.

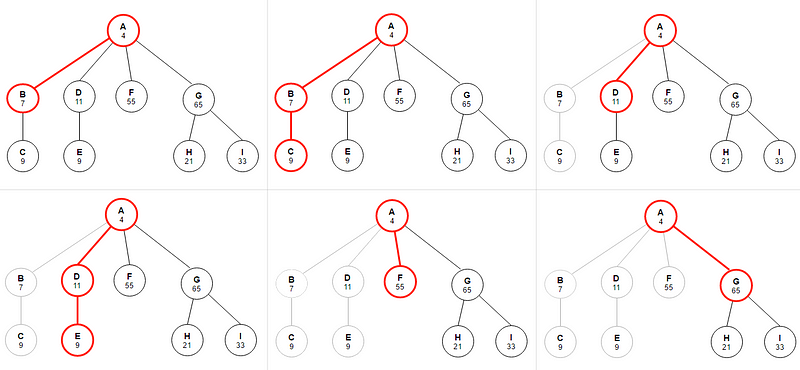

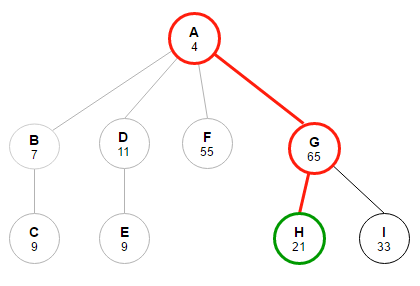

So here is how we are going to go about it:

- First, check node A.

- If it’s not what we’re looking for, we can then go to B, then to C.

- No node on our path satisfies the equality and there is nowhere to go from here, so we backtrack to A.

- Then we check D and E. No luck.

- Backtrack. F.

- Backtrack again. Check G. Still no luck.

But we still have places to go. Finally H. This is the node we’re looking for.

And here is the simple implementation:function find(node, value) {

if (node.value === value) {

return node;

} else {

for (let i = 0; i < node.children.length; i++) {

let found = find(node.children[i], value);

if (found !== null) {

return found;

}

}

return null;

}

}

assert.equal(find(tree, 21).name, 'H');

Designing a solution

A common mistake beginners make when designing a solution to a recursive problem is to try to imagine what happens inside the recursive call, instead of just trusting that it will return the correct result. In the problem with nested arrays for the solutionif (Array.isArray(a[i])) {

result += sum(a[i])

do not think what will happen once sum function is executed. This is not a useful way to think about recursion. Instead trust that it returns correct sum for all elements of an array a[i]. Also, do not think about a recursive program as a series of execution steps and try to reconstruct execution tree in your head. For some complex problems, this will be very difficult and won’t help you come up with the solution.

When you start working on a solution, think about how the original problem can be represented as a simpler problem plus some additional operations. Identifying this simpler problem is arguably the most difficult part of solving a recursive problem. This may be trivial for some easy problems like the ones we used in the examples above, but for many harder problems discerning a pattern requires skills. The more you practice, the better you get at it.

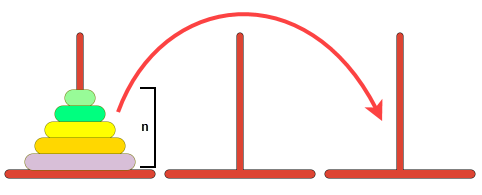

Once you identified the simpler problem proceed to find the simplest problem your function will need to solve. This simplest problem is called base case. It is usually represented as a form of a condition which terminates recursion. In our previous examples, it comes in the form of a for loop that checks whether there are elements in an array (sum) or children in a node (find). Sometimes, in easy problems, the simpler problem that helps you solve the original problem is the also the base case. But it’s not the case with harder problems like this famous “Tower of Hanoi” problem:

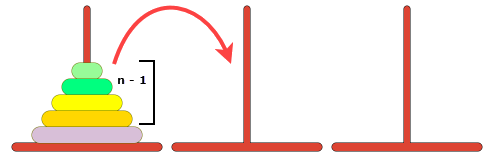

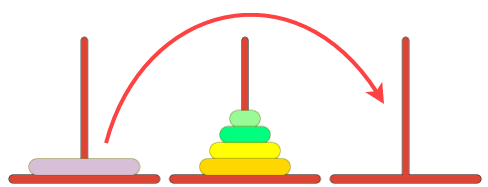

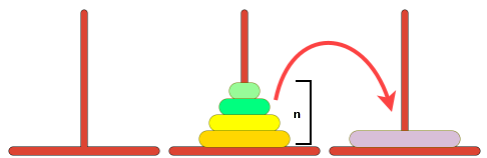

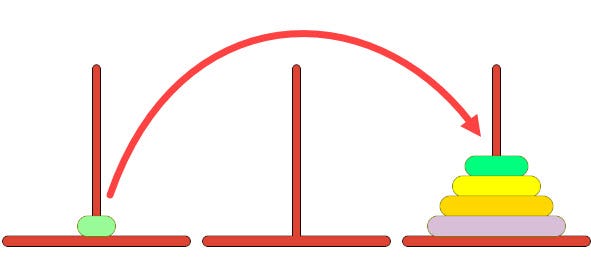

You have three rods and a number of disks of different sizes, which can be moved onto any rod. You start with the disks in a neat stack in ascending order of size on one rod. The objective of the game is to move all the disks over to Tower 3. But you can move only one disk at a time and cannot place a larger disk onto a smaller disk.

This simpler problem you’re required to see here is this:

- Move

n-1disks to the auxiliary rod.

2. Move the last disk from source to target rod.

3. After you’ve moved the last disk, the remaining disks from the auxiliary rod can be moved to the target rod.

It’s important here to not think through steps how the disks are moved to the auxiliary rod but to assume that if they are already moved there, we can move the last disk and then move the remaining disks. So let’s write the code for this case:function move(n, src, aux, dest) {

// move all disks but the last from source to auxiliary rod,

// that's why aux and dest rods are swapped in a function call

// so that aux rod becomes the destination

move(n - 1, src, dest, aux);

// move the last disk from source to destination rod

dest.push(src.pop());

// move the remaining disks from auxiliary to target rod,

// that's why aux and src rods are swapped in a function call

// so that auxiliary rod becomes the source

move(n - 1, aux, src, dest);

}

Now that we have a simpler problem, we need to find the simplest base case. And it’s probably easy to spot it:

If we have one disk left, simply move it to target rod:function move(n, src, aux, dest) {

if (n === 1) {

dest.push(src.pop());

} else {

move(n - 1, src, dest, aux);

dest.push(src.pop());

move(n - 1, aux, src, dest);

}

}

And that’s the base case that ends the recursion. And it’s not the same simpler problem that helps you solve the original problem.

Now, try to apply what you’ve learnt above to the following problems:

- Finding sum of nested arrays

Write a function that sums all numbers in an array that can have nested sub-arrays. Do not use loops.

2. Generating binary strings

Write a function that generates all possible combinations of 1 and 0 for n bits. For example, if the function receives2as the number of bits, it should produce the following 4 combinations:00,01,10,11. You cannot use any mathematical operators.

When trying to come up with the solution, try to think about the solution by identifying simpler problem and base case, and not by constructing step by step execution flow. Also, try thinking that you’re now looking at the intermediate step, what is the next operation you should perform to progress towards the solution.

Check solutions and explanations in the end of the article.

Tail-call optimization

You may have heard the term call stack. It’s mostly used during debugging to understand how the function that produced an error got called. So if you have a code like that in the file index.js :function a(n) {

let a = 1;

return a + n;

}

function b(n) {

let b = 5;

let value = a(n); // line B

return b + value;

}

function c() {

let c = 3;

let v = b(c); // line C

console.log(v);

}

c(); // line A

and put a breakpoint inside a, you will have a call-stack that looks something like that:a() (return to: {b(): B}, locals: {a=1, n=3})

b() (return to: {c(): C}, locals: {b=5, n=3})

c() (return to: {index.js: A}, locals: {c=3, v=undefined})

Which states that the function a was called from b and b from c. This is where the name call stack comes from — a stack of function calls. Each entry in the stack is called stack frame and holds among other things the following information: local variables and return address (to return to when current function exits). What’s important is that the number and size of frames on the stack is limited. It means that if you continue to call functions enough times you’ll get the stack overflow error. This limit is not fixed and varies from environment to environment and depends on the frame size of each individual function.

Recursive function keeps calling itself many times so there’s a potential risk of stack overflow error. For example, this simple recursive function calculates a factorial of a number:function fact(n) {

if (n === 0 || n === 1) {

return 1;

}

return n * fact(n - 1);

}

If we pass a quite large number, for example, 100 000, we’ll get the error in most environments. This recursive implementation of factorial is usually not recommended as an example of recursion because the same result can be much easily achieved using iterative solutions. Besides potential stack overflow error, this recursive solution adds overhead to the performance by using extra stack frames and consequently taking up more memory.

However, this is the preferred solution for many functional languages like Lisp and Scheme. So how do they avoid the above-mentioned problems? The answer is tail-call optimization. Let’s take a look at the refactored code of the example of stack presented above:function a(n, p) {

let a = 1;

return a + n + p;

}

function b(n) {

let b = 5;

return a(n, b);

}

function c() {

let c = 3;

let v = b(c); // line C

console.log(v);

}

c(); // line A

It now seems that there is no point in creating a stack frame for the function b because all it does is calls a and doesn’t perform any action after that. The compiler notices that and optimizes these calls to not create a stack frame for b. The optimized stack looks like this now:a() (return to: {c(): C}, locals: {a=1, n=3, p=5})

c() (return to: {index.js: A}, locals: {c=3, v=undefined})

Take a look at the differences in the function b before and after refactoring:// without tail-call optimization

let value = a(n);

return b + value;// with tail-call optimization

return a(n, b);

So the main difference is that there is no other action after function a returns. Let’s rewrite our factorial function to be eligible for tail-call optimization:function fact(acc, n) {

if (n === 1) {

return acc;

} else {

return fact(acc * n, n - 1);

}

}

As you can see, instead of taking the return value and calculating the result after the recursive call returns, we calculate it first and pass along to the next recursive call. So in the first non-tail optimized implementation, you perform your recursive calls first, and then you take the return value of the recursive call and calculate the result. In this way, you don’t get the result of your calculation until you have returned from every recursive call.

To transform the implementation into tail-recursion, you perform your calculations first, and then you execute the recursive call, passing the results of your current step to the next recursive step. This results in the last recursive call simply returning accumulated value when the condition is met. Basically, the return value of any given recursive step is the same as the return value of the next recursive call. The consequence of this is that once you are ready to perform your next recursive step, you don’t need the current stack frame anymore.

In some functional languages, tail-call optimization can also be achieved using continuation-passing style (CPS) — a.k.a callbacks. When using callbacks there is no need for return statements and so the compiler can optimize recursive calls. Although JavaScript supports callbacks model very well, it currently doesn’t support tail-call optimization through CPS.

Solutions

So, here is the first problem:

Write a function that sums all numbers in an array that can have nested sub-arrays. Do not use loops.

We can start by identifying the simpler problem — which is an array without nested sub-arrays. Let’s ask the same questions to solve this simpler problem:

- What is the simpler problem? The simpler problem is when I have a sum of

n-1elements and only need to add the current element to this sum. - What is the simplest case? The simplest case is when no elements left to be added — return

0.

So here is the implementation:function sum(a, i) {

if (i < 0) {

return 0;

} else {

return a[i] + sum(a, i - 1);

}

}let input = [1, 2, 0, 3];assert.equal(sum(input, input.length-1), 6);

Now, we have solved a simpler problem with no nested arrays. We need to account for nested arrays. We need to check if an element is an array and if so, just run sum function against it. The important thing here is to not forget to obtain the sum of elements in the nested sub-array and add it to the resulting value. So here is the final implementation:function sum(a, i) {

if (i < 0) {

return 0;

}

let current = a[i];

if (Array.isArray(a[i])) {

current = sum(a[i], a[i].length - 1);

}

return current + sum(a, i - 1);

}

let input = [1, 2, [1, 2], 3, [5]];assert.equal(sum(input, input.length - 1), 14);

Let’s now review the second problem:

Write a function that generates all possible combinations of 1 and 0 for n bits. For example, if the function receives2as the number of bits, it should produce the following 4 combinations:00,01,10,11. You cannot use any mathematical operators.

What is the simplest case here? We need to produce strings for only one bit. For this, we will have two strings 1 and 0. So, we have a function that outputs 1 and 0 if the number of bits is 1. Let’s write it down assuming there’s a global a variable holding an array:function binary(n) {

if (n === 1) {

a[n - 1] = 0;

console.log(a.join(''));

a[n - 1] = 1;

console.log(a.join(''));

}

}

This current implementation contains duplicate console.log statement, so we can improve the code by doing the logging as the last operation when there are no more bits to set. Let’s rewrite the implementation:function binary(i) {

if (i === 0) {

console.log(a.join(''));

} else {

a[i - 1] = 0;

binary(i - 1);

a[i - 1] = 1;

binary(i - 1);

}

}

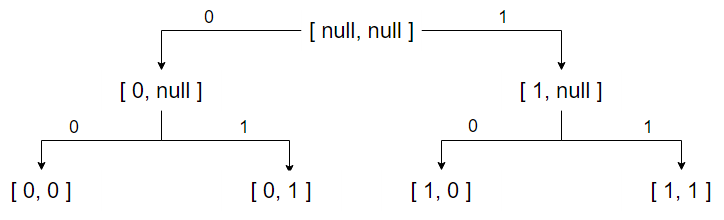

Now, let’s see what combinations are going to be there for 2 bits.

So, here we begin with no bits set. Then we’re settings bit to 0 for the n bit. Then we do the same for n-1 bit. We follow this pattern until there’re no more bits to set. We print the combination and backtrack one level up. Then we set the n bit to 1. It’s clear that at each step the function is only concerned with setting the current bit and calling the function to process the remaining bits.

And this is what we already have in our implementation for processing one bit. As it turns out, by simply refactoring the base case we’ve arrived at the solution that will work for any number of bits.